In the late 1990s a small Canadian junior mining company bought an exploration property in southern Peru with a plan to capitalize on the newly opened market after two decades of internal conflict and civil war.

Just 100 km north of the Atacama Desert, the driest place on earth, the property consisted of hard earthen mountains, trickling riverbeds and the occasional cactus. Nestled in one rocky corner was a small, half-built gold processing plant. The mill came with the exploration property, almost as an afterthought, a redundancy that was easier to give away than tear down.

The junior was headed by Jean Martineau, a French-Canadian pulp and paper mill operator turned broker turned CEO.

Jean’s days as a broker had left him with one overriding view of the junior mining sector: it ran on a terrible business model - constantly raising money, diluting value, and rarely benefitting investors.

An experienced operator, Martineau decided the best way to fund exploration was to generate cash by getting the small mill on site up and running, purchasing ore from nearby small-scale miners as feed and processing it at a profit.

He was warned off by colleagues, criticized by the market and doubted by industry, but the stubborn Frenchman ploughed ahead anyway.

Martineau was looking for a business model that would fund exploration without the need to continually go back to the market. It took nearly a decade and almost bankrupted the company, but he did it.

What the CEO of Dynacor didn’t know at the time was that he was blazing a trail for a new industry within the junior market - one that would be copied, emulated, hyped and would eventually become one of the “hottest stories” on the market: toll milling.

If you’ve followed the junior mining space over the past few years, you’ve undoubtedly heard stories of the opportunities surrounding Peru’s blossoming toll milling industry.

Toll milling’s rise to prominence is largely due to the success of Dynacor and recent regulatory changes in Peru legalizing small-scale mining. You might have also heard that toll milling is a way to turn a junior miner cash-flow positive with relatively little upfront cost and to make it capable of funding future exploration without diluting shareholder value.

Last month I had the opportunity to spend some time with the CEOs of three of the space’s current and would-be leaders: Jean Martineau of Dynacor Gold Mines, Greg Smith of Anthem United Inc. and Len Clough of Standard Tolling Corp. I then travelled to southern Peru to see the sites in action and meet the Anthem and Dynacor teams.

What I found: toll milling offers tremendous opportunity for great management teams, with the right contacts in the right locations. For the rest, it offers a good story followed by inevitable pitfalls.

NOTE: I’ve written this article out of interest in the toll milling industry. I’ve received no compensation for the article, and I covered all of my travel expenses and accommodations, except for car rides to site. At this time I do not own shares in any of the companies discussed, although I may purchase shares in one or more in the future.

What is Toll Milling?

Toll milling has likely existed as long as there has been mining. The concept is straightforward: someone buys ore from a miner, processes it and (hopefully) makes a profit by selling the finished product. It can be done with nearly any metal, but gold is the most common.

This means that today, if a toll miller can assay, purchase, process and transport ore at a cost of $1,000 per ounce and sell it for $1,200 per ounce he’s making a $200 (20%) profit.

Simple.

So simple that Canadian juniors, unable to raise cash and desperate for a good story, have flocked to the space over the past two years.

Like most things in the industry, toll milling is a lot more complicated than it appears at first glance. To understand how toll millers work, you first need to understand their clients: The Artisanal Miners

Artisanal miners - who are they?

An artisanal or small-scale miner (ASM) is essentially a subsistence miner; someone who is not employed by a company but rather works a plot of land that he may or may not own, mining or panning by hand. The practice is common throughout the developing world, and it’s been estimated by the ICMM (International Council on Mining and Metals) that as many as 100 million people worldwide rely on ASM for their livelihood.

Artisanal, or informal mining as it’s often referred to in Peru, has been a common practice in South America since the Inca began pulling gold out of the rivers and Andes hundreds of years ago.

In Peru small-scale miners work individually or in small groups to mine relatively small claims by hand. The more advanced groups have formed collectives working together to mine claims, sharing the profits and expenses. Typically this style of mining involves using minimal equipment such as hand-held pneumatic drills, dynamite, picks, shovels and wheelbarrows. The more advanced miners, often those with outside backing, may utilize crushers, skips and other mechanized equipment to improve production and recovery.

Generally these miners will pan for gold or mine by following narrow veins into the bedrock. Mining these veins often involves excavating a tunnel so narrow that miners enter crouched and in single file. It would be uneconomic to mine these veins by conventional methods.

In many ways artisanal miners are similar to farmers in the sense that they generally own, rent or simply take a plot of land and live off what they can pull out of the ground. They’re independent and sometimes desperate; having operated outside the law for so long, they can be wary of authority and government. Small-scale miners can range from being quite wealthy to barely subsiding, depending on the property, their skill at extracting ore, and where they sit in the mining process (owner vs. laborer).

Unlike farming, artisanal mining is an industry that has been repeatedly tied to corruption, narcotics, child labor, environmental devastation and human rights abuses.

Funding for small-scale miners is rumored to come from a range of nefarious sources such as Narcos looking to launder money (Peru recently surpassed Colombia as South America’s premier cocaine exporter), Chinese and Russian mafias, and even North Korea.

Why Peru?

Because of these issues, and in an effort to receive its share of the billions of untaxed dollars generated by artisanal miners, Peru has led the charge in South America to legitimize the Informal mining sector.

In 2012 the Peruvian government launched a formalization program to register and license previously illegal small-scale miners and toll mills. Once registered, the miners (and mills) declare the work they are doing, pay taxes, and operate in much the same way as any small business.

Because of this, foreign (and local) companies have rushed in to take advantage of the processes and quickly permit small-scale mills within the temporary permitting window that exists during the process. Under this process, administered regionally, companies can permit a small-scale mill of up to 350 tpd capacity, in a matter of months as opposed to years.

In addition to providing the government with millions in tax dollars, legalization has several enormous benefits for the country and the miners. Small-scale mining is not going away in Peru; legalizing it legitimizes and regulates the work being done. Legitimizing provides clear environmental guidelines miners must follow and the increased transparency helps push out corruption and criminal elements such as the drug cartels, who control much of the industry.

The transition, however, has not been without challenges.

Convincing hundreds of thousands of people who have been working illegally, often for decades, that they should declare themselves to a government that has spent years trying to shut them down is no easy task. Add to this the expensive bureaucratic nightmare that is the registration process and the fact that many of the would-be participants live in extremely remote areas, often possessing little to no formal education, and you begin to see the challenges.

It should come as no surprise that the government has had to extend the deadline for registration, and it is widely believed that they will have to do so again.

However, the government has been offering support and taking steps to simplify the registration process. To date, 70,000 of the miners have been coaxed out and registered; meaning they are now taxpaying citizens who must sell their ore to legal, licensed milling operations.

Challenges

While there are typical challenges associated with operating any processing plant, toll milling has two unique challenges: Metallurgy and Supply. The two are closely related.

Supply

As Toll Millers do not have their own mine, they have far less control over their ore supply or “ore stream” than traditional mining companies. They must obtain ore from miners lacking the facilities to process it themselves. In the case of Peru, that means relying on dozens or even hundreds of suppliers to meet a mill’s daily feed requirements.

Dynacor, for example, currently processes 250 tpd and requires 270 suppliers to do it.

To succeed, toll millers must develop trusting, long-term relationships with numerous suppliers to ensure a continuous ore stream. Suppliers often truck ore over 1,500 kilometres to reach mills, passing numerous plants (read: competitors) along the way, that are constantly attempting to offer the best price to get their business.

Securing high-quality, reliable ore is and will continue to be the greatest challenge of toll milling. The ability to do so will undoubtedly distinguish the winners from the losers.

Many toll millers cite contracts with one group of miners or another as assurance of ore supply. But as both Greg Smith, CEO of Anthem United, and Jean Martineau pointed out to me: the contracts have no teeth. It’s essentially impossible to force a small-scale miner, who has likely been mining illegally for decades prior to formalization and is still only loosely monitored by the government, to give you his ore if he doesn’t want to.

So how do toll millers find reliable suppliers with high-quality ore?

The real key to success is building relationships, earning miners’ trust and proving that they will receive a fair price and great treatment.

This requires two things: Money and Time. Toll millers must constantly pay miners a fair price, on time, which requires cash, well-designed purchasing contracts and access to a highly accurate lab to ensure quality assaying and metallurgical testing.

Metallurgy

I consider the most underappreciated challenge facing toll millers to be metallurgy and recovery. Unlike traditional miners who know their deposit, have complete control of the feed, and can plan production for years in advance, toll millers rely on hundreds of suppliers producing material at different rates, at a variety of grades and from a host of deposits each producing material with unique metallurgical properties.

A mining company can customize their processing plant to ensure optimal recovery from the ore produced by its mine. Toll millers, on the other hand, must produce an optimized feed for a generic mill - combining numerous sources of ore each of varying grade and metallurgical properties.

I’d liken producing this custom ore feed to baking a cake. You need to bake the same cake every day, but each day with different ingredients.

Most toll millers claim to be aiming for 90 – 95% recovery, a feat that took Dynacor years of experimentation and relationship-building with suppliers to accomplish.

What will make or break a company is its ability to accurately and consistently establish the grade of ore upon delivery and achieve their target recovery. This will enable them to pay the right price for a given ore delivery and ensure they’re not losing money.

And they must do this again and again.

Economics

Size Matters

A common theme among companies moving into the space is this:

“We’ll be starting production at 50 tpd and using revenue to ramp up to 100 tpd.”

A closer look at the numbers shows that many companies are assuming gross profits of 15% - 20% (similar to Dynacor).

This is likely wrong.

Let’s ignore for a moment that it took Dynacor the better part of a decade to optimize their operations and achieve this (consistent supply, metallurgy, recovery, etc.). Assuming that newcomers can emulate this success out of the gate -- which is a leap -- there is still a glaring issue: Economies of Scale.

Simply put: producing 200 tpd is not twice as expensive as producing 100 tpd.

There are overheads and expenses that remain consistent or increase at a rate much lower than 1:1, particularly in a public company. These include:

- General overhead

- Cost of paying management

- Office space

- Reporting requirements

- Legal costs

- Regulatory requirements

- Costs associated with sourcing ore

- All the other expenses required to run a public mining company

In addition, it doesn’t take twice as many people to run a 200 tpd operation as a 100 tpd operation. Smaller operations require nearly the same number of technical staff (the highest paid) and support staff (cooks, cleaners, etc). They require less operators – but the costs associated with feeding, housing and transporting them decrease nominally.

For smaller operations, overhead expenses are going to eat up a larger percentage of the profit. At 100 tpd, they may eat up all the profit.

Additionally, since small mills are relatively cheap to build/buy, they’ll be competing with a host of private operators that run on similar economies of scale … but don’t have to worry about all the expenses associated with running a public company.

Since almost every company entering the space references Dynacor as a model, here’s what the CEO of Dynacor says on this subject:

“At 100 tpd, as a public company, we couldn’t break even. To survive we increased the throughput of the operation as much as we could, cut the operations crew to the minimal number of people, and the entire senior management took a 25% pay cut.”

Dynacore stuck with that strategy until they could afford to expand the mill and increase throughput to a profitable scale.

Be wary of companies not planning on processing more than 150 tpd.

There is not room for everyone

Given the gold rush mentality currently hitting the Peruvian toll milling scene, there are a host of companies moving in to set up shop. Most claim they’ve run the numbers, that there is plenty of high-quality feed, “it’s a money maker,” etc.

Let’s do a quick back-of-the-envelope calculation to check into this:

1. It’s commonly stated that there are 100,000 – 500,000 informal miners operating in Peru. Despite that staggering range in the estimate this number is irrelevant. Informal miners are illegal miners and toll milling operations set up by foreign companies can only legally purchase ore from miners that have formalized and registered under the government’s scheme.

2. To date, approximately 70,000 miners have registered under the government’s formalization program, but even that number is misleading. Of the 70,000, only 31,000 have followed the process to the point where they’ve received their RUC number, which is essentially a tax number required to sell ore.

3. Therefore legal toll millers can currently only purchase ore from a maximum of 31,000 miners, assuming they are all operating (they aren’t) and producing ore of a grade and quality which you’d actually want to purchase (they don’t).

4. Estimates vary, but it should be assumed that the average miner can extract approximately 150 kg of ore per day (this estimate was provided by Jean Martineau based on his experience in the region).

5. That means that the best-case scenario leaves toll millers with (150 kg x 31,000 miners) 4,650,000 kg – or 4,650 tpd available nationwide.

6. The average company attempting to move into the space claims they will produce between 100 – 350 tpd. But since operations below 150 tpd won’t work we’ll assume an average of 250 tpd.

7. At that rate Peru can reasonably accommodate (4,650/250) 18 toll milling operations - total.

Understand that this is a very simplified calculation and is intended to help readers visualize the size, scale, and capacity of the industry as it stands.

It also doesn’t account for the dozens (or maybe 100’s) of private small-scale mills (some legal, many illegal) competing for ore. The government has been aggressively working to shut down illegal operators, even going so far as to blow up mills and equipment, but they still exist throughout the country.

More miners could register with the government in the future, but it is not a simple process and will not happen quickly.

To secure ore, toll millers will need to become a partner of choice for miners or have a clear advantage over competitors.

Keys to Success

Transparency

Miners will consistently bring ore to millers they trust. In an industry ripe with corruption and general shadiness, the key to building trust is transparency. Miners must know they are getting paid a fair price for their ore, every time.

This means having a lab on site that can accurately assay the grade and test the metallurgical properties of the ore. This allows miners to observe the processes and test their ore independently if they wish.

Value

At the end of the day the miners will be looking for a fair, consistent price, and to be paid quickly. Companies must utilize pricing models that provide them with the target profits but also offer miners good value. Larger mills will have an easier time with this simply due to economies of scale. Companies must also have sufficient working capital to pay upfront, limiting wait times for miners.

Incentives

Many of the companies I spoke with are looking into offering miners incentives to work with them. Incentives could be anything from offering miners micro-loans to purchase equipment, helping them complete the formalization processes or assisting them with environmental best practices.

Several toll millers are looking to partner with international organizations or governments to help offer their suppliers superior service and establish themselves as a preferred partner.

Location

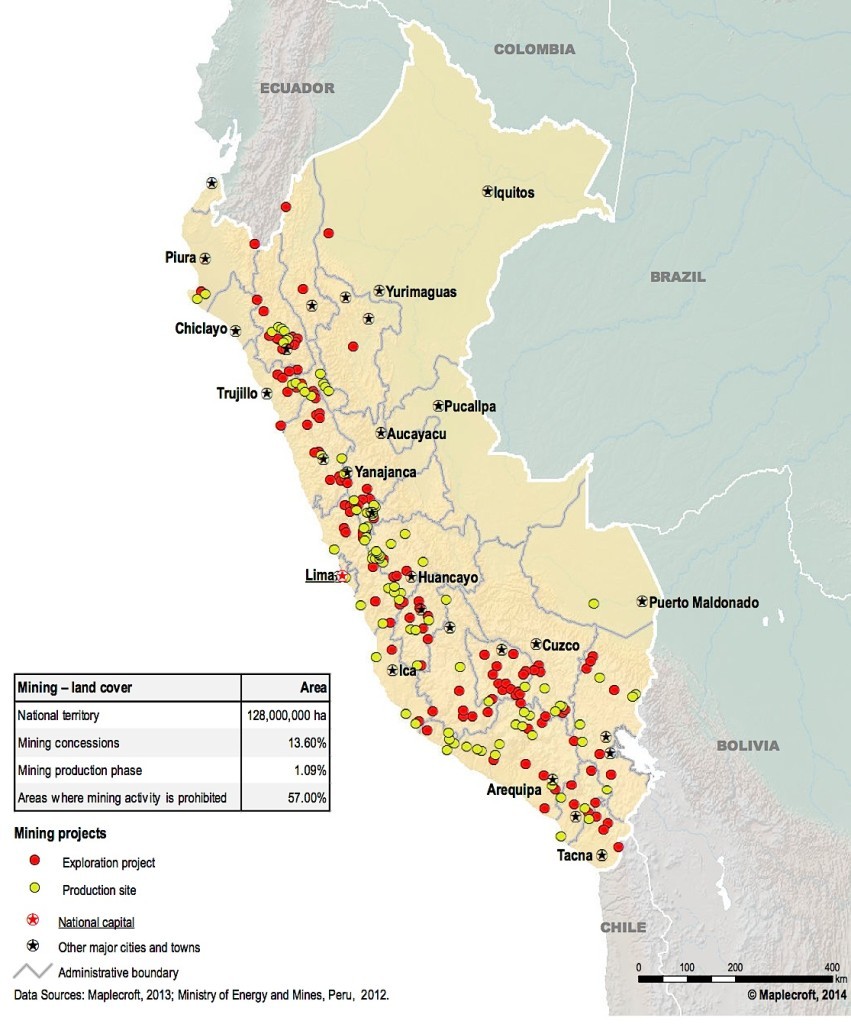

As shown by the map below, mining occurs all across Peru.

However, the vast majority of toll mills, especially legal/permitted mills, are around Chala and Arequipa in the South. This means that miners in the North often drive over 1,500 km to reach quality mills.

Well-operated, transparent mills in the north or other under-served regions will have a massive advantage when it comes to getting business.

They may also have the opportunity to purchase slightly lower grade ore from the region at a discount, because it’s simply not economic to ship to the south and was previously considered waste.

The Players

When it comes to toll mill operators, there are three essential ingredients for success:

An excellent, experienced management team with a clear vision

An even better technical team with the ability to face the inevitable metallurgical challenges

Enough money to play the long game. This means being able to buy ore, build the plant and spend the time ramping up and getting the metallurgy right without requiring a quick profit to pay back loans. It also means being able to take the time to build relationships and create the right partnerships.

As with any good story, the toll milling saga has a host of players. Following are three that I believe have the greatest potential to succeed in the space and are worth keeping your eye on.

The Trailblazer - Dynacor Gold Mines (DNG; $2.08)

Dynacore leads the list because it has a track record of success, with plans for growth.

The company also embodies the best of mining and exploration - they saw an opportunity where no one else did and despite challenges and naysayers, created real value. The management and investors weren’t trying to get rich quick; they stuck to their vision and as a result, they’ve changed the industry.

Dynacor Gold Mines began as a spinoff from Dynacor Mines in 2006. The original company moved into Peru in the mid-1990s and inherited a small half-complete 50 tpd mill on one of their exploration properties. That mill was revitalized and became their flagship 250 tpd Huanca ore-processing plant.

Huanca has been cash flow positive since 2007, and has consistently turned a profit for the past several years. With the success of their first mill under their belt, Dynacor is now constructing its second plant - a custom-built 300 tpd operation in Chala, a short drive from the Pan Am highway.

A quick look at the facts:

Financial

- They have a market cap of over $76M, with just 36,245,111 shares issued

- They’ve been profitable the past three years, with annual EPS averaging $0.21

- They have nearly $21M in working capital

- And NO DEBT!

Technical

- Dynacor has operated its 250 tpd Huanca plant for over 10 years; they’ve managed to consistently secure feed averaging 1 ounce per tonne and have obtained a 94% recovery for the past several years.

- This plant has been expanded from its original capacity, 50 tpd, to 250 tpd. Although it might not be particularly efficient, it is extremely effective.

- After two years in the permitting process, Dynacor is about to begin the construction of a new 300 tpd plant at a cost of $12.7M, bringing total production to 550 tpd.

- In addition, the new plant is designed to be ramped up in two stages to 600 tpd over the next few years. This could eventually provide Dynacor with a total milling capacity of 850 tpd.

- The new Chala plant has been custom built to meet their needs. It is expected to be much more efficient and require less labour per tonne processed.

- Unlike the Huanca mill, the new Chala operation is just minutes off the Pan American highway. This means that they will be far more accessible to suppliers (the drive to the Huanca plant is not an easy one).

- All of this means that Dynacor will be able to produce more for less, and they have the experience, team and supply chain in place to do it.

The Risks

- The lifespan of the Huanca operation is limited by space on the property to store tailings, and the mill is currently running out of room.

- They are currently permitted for one more year’s worth of conventional tailings disposal, subsequent to which they plan to switch to dry-stack tailings, providing an additional 2- 4 years of operation.

- Dynacor has yet to apply for or receive these permits, but they plan to shortly. Mr. Martineau is confident it won’t be a problem; it does however increase uncertainty regarding the longevity of the Huanca plant.

- Another risk is that when the Chala plant is up and running, the two operations could cannibalize one another if there is insufficient ore available to fully feed both. However, this is unlikely given Dynacor’s extensive relationships with miners and experience in the region.

The Mitigation

- Realistically the risk is small. Even if Dynacor only gets one more year out of the existing Huanca plant, they have the capital and expertise to ensure the new mill is up and running by that time.

- The new mill will produce 300 tpd, a 20% increase over the current production, and it will do so at a lower operating cost per tonne milled.

- However, unlike any of their competitors, Dynacor has permitted their plant as a large-scale operation (which is why it took two years). This means that there is no limit set on plant capacity, so they intend to ramp the new plant up to 600 tpd over the next few years.

The Result

- Assuming no tailings permitting advances at Huanca, this means that in the next year Dynacor will be processing a minimum of 20% more feed. They will accomplish this by replicating a proven process, and can completely cover the associated capital costs.

- If this is reflected in the earnings per share (three-year average of $0.21 EPS) it would mean an increase of 20% to $0.25 EPS.

- Best-case scenario: Dynacor hits 600 tpd output in the next couple of years and thus increases output by 2.4 times, which could increase EPS to $0.50.

Conclusion

In my opinion Dynacor is a win, by how much is simply a matter of execution. They have plenty of capital, no debt and are growing a proven business model (in addition, the company is buying back shares at an average price of $1.50). The downside is minimal, and unlike most junior explorers the upside is measurable. Don’t expect Dynacor’s value to double overnight on the back of a drill hole or a good story, but expect the company to continue to grow steadily and build lasting value.

The Rising Star - Anthem United Inc. (AFY; $0.40 )

Anthem United, the soon-to-be-largest toll miller in Peru, is currently building its 350 tpd operation in Arequipa, minutes off the Pan American highway.

Anthem seems best known for, well… being unknown.

During my trip around Peru, and in the many conversations I’ve had in Vancouver prior to writing this article, I found few people in industry, government or finance who had heard much about Anthem. In fact, many of their soon-to-be-competitors were not aware of them at all.

And Anthem wouldn’t have it any other way.

As CEO Greg Smith succinctly put it during our first conversation, “I’m a miner, not a marketer.” And he has the track record to prove it.

Smith got his start in KPMG’s mining division as a chartered accountant, then made the jump to Goldcorp where he worked under the leadership of Ian Telfer. In 2006, he became CFO of Minefinders, where he was integral to the development and eventual sale of Minefinders and its Dolores project to Pan American Silver for a staggering $1.5B in 2012. Following this success, Smith took the CEO reins at Esperanza Resources and a year and a half later, in August 2013, sold it for $70M plus warrants to Alamos Gold. Most recently, Smith acted as director and chairman of the special committee of Premier Royalty throughout its sale to Sandstorm Gold for $30M in September 2013.

Given Smith’s track record, as well as backing by Marcel de Groot’s Pathway Capital, any project he runs deserves to be taken very seriously.

The truth is, Anthem has little need for publicity. A quick look at the books shows why:

- Anthem currently has a market cap of $27.5M, with nearly 68.7M shares issued and trading at $0.40 a share.

- Currently management and directors hold a whopping 41% of the stock, with Smith personally holding 16.7% of the shares. And they aren't taking a salary.

It’s clear that Anthem management is confident in the business they are building.

- Anthem’s Koricancha mill is estimated to cost $10M, including initial ore purchase, and is fully funded.

- Anthem raised $5M in an equity financing in April 2014, a further $5M in committed funding from SA Targeted Investing Corp., an independent third party in February 2014 through a gold sales agreement; and a $2M ore purchase credit facility with SA Targeted Investing Corp.

Anthem decided to move into the toll milling business when they were approached by EMC Green Group, a Peruvian based company headed by Andy Pooler (former EVP, Operations, at Pan American Silver). Smith says he was originally reluctant to enter the space but changed his mind after running the numbers.

“We saw there is a HUGE delta between number of registered small-scale miners looking to sell ore, and legal milling capacity in the country,” says Smith, referring to the fact that registered miners must sell ore to a registered mill in order to maintain their permits.

After recognizing the opportunity, Anthem partnered with EMC, who now own 25% of Anthem and are fully responsible for on site construction and operations.

With their custom-built 350 tpd mill coming online at the end of June, Anthem stands to be the largest toll miller in the country. Smith estimates that at $1,200 oz. gold and an average feed grade of 20 gpt, Anthem will generate an average of $10.7M after-tax free cash flow annually over the first 5 years.

Anthem has the cash, technical team and management chops to construct and operate a first-class toll mill. But this left one glaring question I had to ask Mr. Smith: Why does a miner driving his truck full of high-grade ore down the Pan Am highway choose Anthem instead of one of the dozen other mills in Arequipa?

Smith, unfazed, provided a list of reason why Anthem would be a top choice:

- Anthem is a legal, fully permitted mill which legal miners are now required to use. Much of their competition in the region is illegal or unpermitted.

- They have the cash to pay miners quickly and fairly.

- They will have a first-rate lab on site (to come online end of june) operated by an independent 3rd party. This will ensure transparency in the assay and metallurgical testing process and fairness of price.

- Easy access: they are minutes from the highway.

Custom-built facilities to ensure efficiency of operations and optimal recovery - They are there for the long haul, Anthem has space for over 20 years of tailings and are committed to creating long-lasting partnerships with their ore suppliers.

- Anthem is currently investigating numerous initiatives and partnerships to give them the tools to improve the lives and work of their supplier.

Mr. Smith was realistic, they’ve been making headway, lining up suppliers for months. They’ve taken and tested samples from over 100 operations around the country and are currently finalizing contracts with suppliers who they believe will be the best fit for Koricancha. But he also knows that the key to ensuring long-term consistent supply of high-quality ore is to develop the right relationships with the best suppliers, and that takes time. Fortunately, given Anthem’s enviable financial position, they have it.

I was impressed after meeting Greg Smith and visiting the Koricancha mill. Mr. Smith is clearly a professional and his breadth of knowledge surrounding the project and the industry is evident.

I believe that there is a finite amount of room in the Peruvian toll milling space, and inevitably there will be more losers than winners. Anthem understands their project, they understand the market, and they’re realistic about the challenges they’ll face. Given the team's impressive track record of creating value, it’s likely they will be one of the winners.

The Dark Horse - Standard Tolling Corp. (TON; $0.14)

Len Clough, the gregarious CEO of Standard Tolling, is not a geologist or an engineer, and he would be the first person to tell you that. Len is a market-focused CEO with a background in wealth management.

He’s also an executive with a clear vision for his company, and he has been tireless when it comes to pulling together one of the most impressive and experienced technical, legal and management teams in the toll milling space.

A quick look at TON’s management line up shows they are a force to be reckoned with:

- Carlos Mirabal - Previously CEO of Orvana Minerals, where he oversaw the ramp-up of milling operations from 650 tpd to 3,000 tpd. Mr. Mirabal also brought 3 of his top engineers/operators with him to TON.

- Alex Davidson - Formerly EVP Exploration and corporate development for Barrick Gold.

- Luis Rodriguez Mariategui Canny - A Peruvian mining lawyer, one of the most experienced and well-connected in the country.

- Carlos H. Fernandez Mazzi - Previously CEO of Minera San Cristobal as well as the W.J. Clinton Foundation’s Clinton Giustra Sustainable Growth Initiative in South America.

When I first met Len last month in his Vancouver office he proudly told me:

“This is it, I’m the only one here, we even contract out our admin service! Everything else is in Peru - In our offices down there, on site down there. That’s where the money goes.”

And it’s true. TON’s management prides themselves on being predominantly a Peruvian company. In addition to this, Len and his team are carefully husbanding every dollar they have. Nearly everything is done in-house, from the majority of the legal work, the engineering and design, to the guys welding and laying the concrete on site. There are no expensive contractors, and everything is carefully monitored by the management team. This includes the sourcing of construction equipment such as multi purpose welders and other tools.

Unlike all of the other companies discussed in this article, who are located in the South of Peru around Chala and Arequipa, TON is located in the North of the country. This is where both their biggest advantage and greatest challenges lie.

TON’s soon-to-be-commissioned 150 tpd mill is located in La Libertad near the city of Huamachuco. Located 10.5 hours from Lima, it’s a historic mining district known for its high grades. It’s also known for corruption, lax regulatory enforcement, various criminal elements, and generally for just being sketchier than the South.

It’s also not easy to get there, but that’s the point.

Because TON is opening up shop in the remote northern mining district, they are offering the remote northern miners the chance to skip the gruelling 1,500 km multi-day drive required to take their ore to the mills in the South.

TON intends to offer miners a legal, transparent milling option in their own backyard, in a region where they have next to no competition. That’s a huge advantage.

Let’s take a quick look at TON:

- In December 2014 they raised $2,642,500 in equity.

- In March 2015 they raised an additional $1.82M..

- Also in December 2014 they purchased an existing mill for $500,000; paying about $100,000 in cash and the rest in shares.

- With the purchase of that mill they inherited $1.3M in debt from the former owner. They are currently paying interest on this debt with the balance due at the end of the year.

- TON has also raised nearly $1.5M in debt, by selling ore notes, and plans to close an additional $750,000 this week. This is essentially cash to purchase ore with. Interest on the ore notes is 10%, as well as a 2% NSR production component. The notes are good for three years.

As it stands, TON has purchased the mill, has nearly $4M in cash in the bank and has just started buying ore (May 18). The plan is to begin producing by the end of June, and currently they are on track to do just that.

What are my concerns with Standard Tolling?

Simply put - size. TON’s mill is designed to run at 100 tpd. Despite being assured that I’m wrong by several people, I still have doubts that any public company can consistently make a profit at 100 tpd.

However, Standard Tolling isn’t capped at 100 tpd. Once they have the mill up and running, the ore supply stabilized and the metallurgy figured out, they plan to start expanding, with Len estimating that the expansion could begin as early as this fall. They definitely have the team to do it, with Mr. Mirabal and his team previously expanding the Orvana operation from 650 tpd to 3,000 tpd.

If they can execute, TON will be more than fine. If they don’t, cash flow may not cover the costs of running the mill and a public company.

Len tells me I’m wrong, and Greg Smith from Anthem thinks I’m probably wrong as well. But Dynacor couldn’t do this, and that’s the model most toll millers are based on. So we’ll have to wait and see.

TON needs to cover interest payments of approximately $350,000 as well as pay back the $1.3M of inherited debt in 2015. But they are currently in a pretty solid position with $4M in cash in the treasury; $2.25M of which is specifically devoted to purchasing ore.

The key now is getting into production and generating cash flow as soon as reasonably possible.

The most important step for TON after reaching production is finding a way to ramp up beyond 100 tpd. After ironing out the kinks at 100 tpd and having some hard data on the economics of the operation, this is unlikely to be an issue. TON has manageable debt and should be generating solid cash flow; it shouldn’t be an issue for them to raise the capital to expand if that’s what is required.

I call TON “the dark horse” because they are totally underappreciated.

It would be shortsighted to assume TON doesn’t have some challenges ahead of them. They will undoubtedly encounter issues in the North that their competitors down south don’t have to put up with. They also need to find a way to grow capacity effectively.

Given their experienced team, geographic advantage and manageable balance sheet they appear undervalued. But that’s alright, because with construction nearly complete and production beginning this summer, TON’s best days are still to come.

Conclusion

To many, toll milling represents a ray of hope in a market where miners have been unable to fund projects or raise investor interest. And while there is opportunity to be had, toll milling remains a poorly understood space, with little information available publicly.

However, if investors take into account the challenges raised in this article and hold would-be toll millers accountable by asking the right questions, there remains tremendous opportunity in the space to create real value.

Follow Jamie Keech on Twitter:

Great site visit this week to Dynacor's and Anthem United's toll milling projects in Peru! #mining #pdac @CEOeditor pic.twitter.com/zL7PJ9ezhE

— Jamie Keech (@Jamie_Keech) April 24, 2015

Oversaturated…

What a hit piece, implies supply crunch, so many errors:

The author takes the CURRENT number of miners,

31,000 and then takes a future production in

each mill 250TPD and claims that means the industry only

supports 18,mills.

Most public companies entering the space are WELL below

100 TPD, while they grow the number of permitted miners

will grow too, the market is fine.